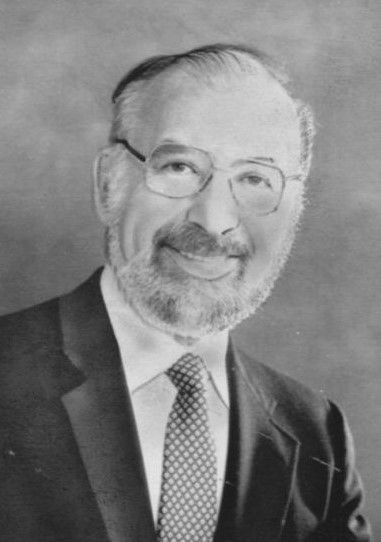

On Honor: Arland D. Williams, Jr.

On January 13, 1982, Arland Williams Jr. was an unassuming, middle aged bank examiner working for the Federal Reserve System. He had two teenaged children and a fiancée waiting for him to return home from a business trip to Washington D.C. A winter storm was enveloping D.C. with freezing temperatures, snow and raging winds. After the meeting, several of William’s colleagues rescheduled their flights. Williams proceeded to the airport, eager to get home to his loved ones.

Flight 90 had 80 people strapped in their seats and ready to go to Atlanta. No doubt they were focused on the day to day thoughts and tasks which consume us all in that moment - thinking about what they needed do when they got home, how their loved ones and friends fared with the day's events, and how good it would feel to sleep in their own bed.

Flight 90 lifted off the ground but, depressed by the winds, clipped the 14th Street Bridge. The airplane hit six cars and a truck, killing four people. It then went hurtling into the frigid, ice covered Potomac River. Seventy-four people never made it to Atlanta.

Bystanders watched helplessly as six survivors from Flight 90 clung to the plane’s tail section, the wind and snow swaying the tail in the inhumane water. Several people attempted rescues, but the distance was too far, the odds too steep against success, and they turned back.

After twenty minutes a Park Police helicopter appeared. The two-man crew undertook a dangerous makeshift rescue operation, imperiling the stability and safety of their own aircraft in the process. The crew lowered a solitary lifeline to the survivors in the water.

A reporter, along with other bystanders, recorded what Arland D. Williams Jr., unidentified at the time, did next:

"He was about 50 years old one of half a dozen survivors clinging to twisted wreckage bobbing in the icy Potomac when the first helicopter arrived. [sic] To the copter's two-man Park Police crew he seemed the most alert. Life vests were dropped, then a flotation ball. The man passed them to the others. On two occasions, the crew recalled last night, he handed away a lifeline from the hovering machine that could have dragged him to safety. The helicopter crew – who rescued five people, the only persons who survived from the jetliner-lifted a woman to the riverbank, then dragged three more persons across the ice to safety. [sic] Then the lifeline saved a woman who was trying to swim away from the sinking wreckage, and the helicopter pilot, Donald W. Usher, returned to the scene, but the man was gone." Washington Post

Five times. Arland D. Williams Jr. intentionally and knowingly made five separate decisions to “hand life over to a stranger” knowing he might lose his in the process.

Five times.

What Arland D. Williams did on that day transformed my life. I confess that I was a self-absorbed, twenty-one-year-old college student with what I now recognize as wildly trivial concerns, when I watched the video of Mr. Williams in the water. He left an impression on my heart and mind that has never left, the impression growing more nuanced and powerful with each of my successive journeys around the sun. Which long ago exceeded the number of journeys he made around the sun.

What is compelling about Mr. Williams’ actions is not simply that he was brave. Or simply that he sacrificed for others. It is that it his actions were driven by something rarely discussed these days: Honor.

As a verb, honor is defined as: “regard with great respect.”[1] Mr. Williams was a graduate of The Citadel. President Reagan, in a commencement address to a graduating class of The Citadel, spoke of Mr. Williams:

No, his moment of truth came not in combat, but on a snow-driven, peacetime day in the nation’s capital in January of 1982. That is the day that the civilian airliner, on which he was a passenger, crashed into a Washington bridge, then plunged into the rough waters of the icy Potomac.

"… News cameramen, watching helplessly, recorded the scene as the man in the water repeatedly handed the rope to the others, refusing to save himself until the first one, then two, then three and four and finally five of his fellow passengers had been rescued. But when the helicopter returned for one final trip, the trip that would rescue the man who passed the rope, it was too late. He had slipped at last beneath the waves with the sinking wreckage –the only one of 79 fatalities in the disaster who lost his life after the accident itself.

For months thereafter, we knew him only as the “unknown hero.” And then an exhaustive Coast Guard investigation conclusively established his identity. Many of you here today know his name well, as I do, for his portrait now hangs with honor –as it indeed should –on this very campus: the campus where he once walked, as you have, through the Summerall Gate and along the Avenue of Remembrance. He was a young first classman with a crisp uniform and a confident stride on a bright spring morning, full of hopes and plans for the future. He never dreamed that his life’s supreme challenge would come in its final moments, some 25 years later, in the bone-chilling waters of an ice-strewn river and surrounded by others who desperately needed help.

But when the challenge came, he was ready. [2]"

When honor is spoken of in our times it is usually in a defensive posture. We speak of having to “defend our honor” or that someone has “questioned our honor.” And people often speak quite loudly when defending their honor, using honor to justify their anger and their questionable tactics in responding to perceived attacks on it. Which misses the mark about what honor really is. Too many people defend their honor in today’s virtual world by employing the same logic underlying duels as a means of defending one’s honor - which mostly resulted not in proving one’s honor but in dying prematurely. Publicly calling people names and avoiding responsibility for one's own words and actions hardly makes us look honorable. We lose our honor in the process of defending it.

Rather, true honor is about holding others in great respect. Mr. Williams made five separate decisions that day to regard with great respect five people he had never met and whom he knew nothing about. Those decisions surely competed with his own honor for his children, fiancée and his innate drive for survival. Which he overrode five separate times in those icy, life sucking waters. No one would have faulted him had he chosen otherwise.

We don’t know what Mr. Williams was thinking in those moments in the water. None of us truly know what we will hold in great respect when tested.

Roger Rosenblatt said of Williams:

So, the man in the water had his own natural powers. He could not make ice storms or freeze the water until it froze the blood. But he could hand life over to a stranger, and that is a power of nature too. The man in the water pitted himself against an implacable, impersonal enemy; he fought it with charity; and he held it to a standoff. He was the best we can do. Roger Rosenblatt essay

Most of us will never face a test of the magnitude that Arland D. Williams faced on the last day of his life. Though each of us are given opportunities every day to hold something or someone in great respect. To honor the abiding good in humanity.

________________________________________________________

Resources:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arland_D._Williams_Jr.

https://www.bing.com/search?q=lenny+skutnik&PC=U316&FORM=CHROMN

https://www.menshealth.com/trending-news/a19525149/heroes-and-self-sacrifice/

[1]https://www.bing.com/search?q=honor&PC=U316&FORM=CHROMN

[2] https://today.citadel.edu/remembering-air-florida-flight-90-hero-arland-williams-jr-citadel-class-of-1957/

Comments powered by Talkyard.